Daily tasks predict hospitalization, death for heart failure patients

(Reuters Health) - Heart failure patients who struggle with daily tasks like bathing or dressing are more likely to be hospitalized and tend to die sooner than those who are more independent, according to a new study.

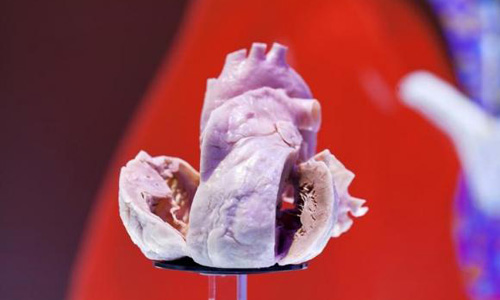

More than five million people in the US have heart failure, meaning their hearts cannot supply enough blood and oxygen to other organs, and about half die within five years of diagnosis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatments include medications, a low-salt diet and daily physical activity.

“I certainly suspected that patients who had increasing difficulty with daily living would be at increased risk for death,” but just how accurately a brief questionnaire could predict hospitalization and death was surprising, said Dr. Shannon Dunlay, lead author of the study and an advanced heart failure cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

For the study, more than 1,000 people with heart failure, and an average age of 75, filled out questionnaires assessing their ability to perform nine activities of daily living, including feeding themselves, dressing, using the toilet, housekeeping, climbing stairs, walking and bathing.

Many of the participants had other health problems like high blood pressure, diabetes or past strokes.

Those who had difficulty with things like bathing or housekeeping were classified as having “moderate difficulty” and those who struggled to feed themselves, use the toilet or dress themselves were classified as having “severe difficulty.”

Almost 60 percent of people reported difficulty with at least one of the nine activities. Around one quarter had moderate difficulty and 13 percent had severe difficulty.

After about three years, more than half of the patients had died and more than 900 had been hospitalized at least once.

The study team adjusted for other illnesses, and found that compared to people with no difficulty with daily activities, those with moderate difficulty were 50 percent more likely to die, and those with severe difficulty were more than twice as likely to die during the study.

Those with moderate or severe difficulty were also more likely to be hospitalized for heart problems or for any reason than those with no difficulty, according to the results published in Circulation: Heart Failure.

People with heart failure tend to be elderly and to have other chronic health conditions, so it can be difficult to separate out what is actually causing the decline in function, Dunlay told Reuters Health.

Doctors do ask their patients about their ability to get around the house and complete daily tasks, but sometimes it can be hard to fit this conversation in with a regular clinic visit, Dunlay said.

Adding a quick questionnaire to the appointment could be a good tool for doctors to assess their patients’ risk of death and hospitalization, which can vary widely for people with heart failure, she said. Some patients do maintain most functional ability, while others will have severe disability.

Many patients become asymptomatic with therapy, according to Dr. Eldrin F. Lewis of the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who wrote an editorial accompanying the new research. “Providers should always aim to get patients to the point where they can do all of the things that they enjoy,” he told Reuters Health by email.

“When I first meet a patient, I often ask them about their hobbies so that I can be realistic with them regarding their ability to eventually do those activities,” he said.

People who were older, female, unmarried and had other health conditions like diabetes, dementia or morbid obesity tended to have more difficulty with daily activities and were therefore at higher risk of hospitalization and death, the authors note.

People who are married have a partner to help with daily tasks and may not notice their functional decline as much as those who are widowed, Dunlay said. Women may have worse outcomes because they tend to be slightly older than men when they develop heart failure.

“Certainly the next step is to better understand whether there are interventions we can do to improve or halt the progression of decline,” both to extend life expectancy and to improve quality of life immediately, Dunlay said.

“Is there an optimal time to catch patients, and intervene with physical therapy?” she said. “For some patients quality of life is as, or more, important than living longer.”

Even before a doctor asks, family are probably already aware that a person with heart failure is having trouble with daily activities, and shouldn’t hesitate to bring it up in the doctor’s office, she said.